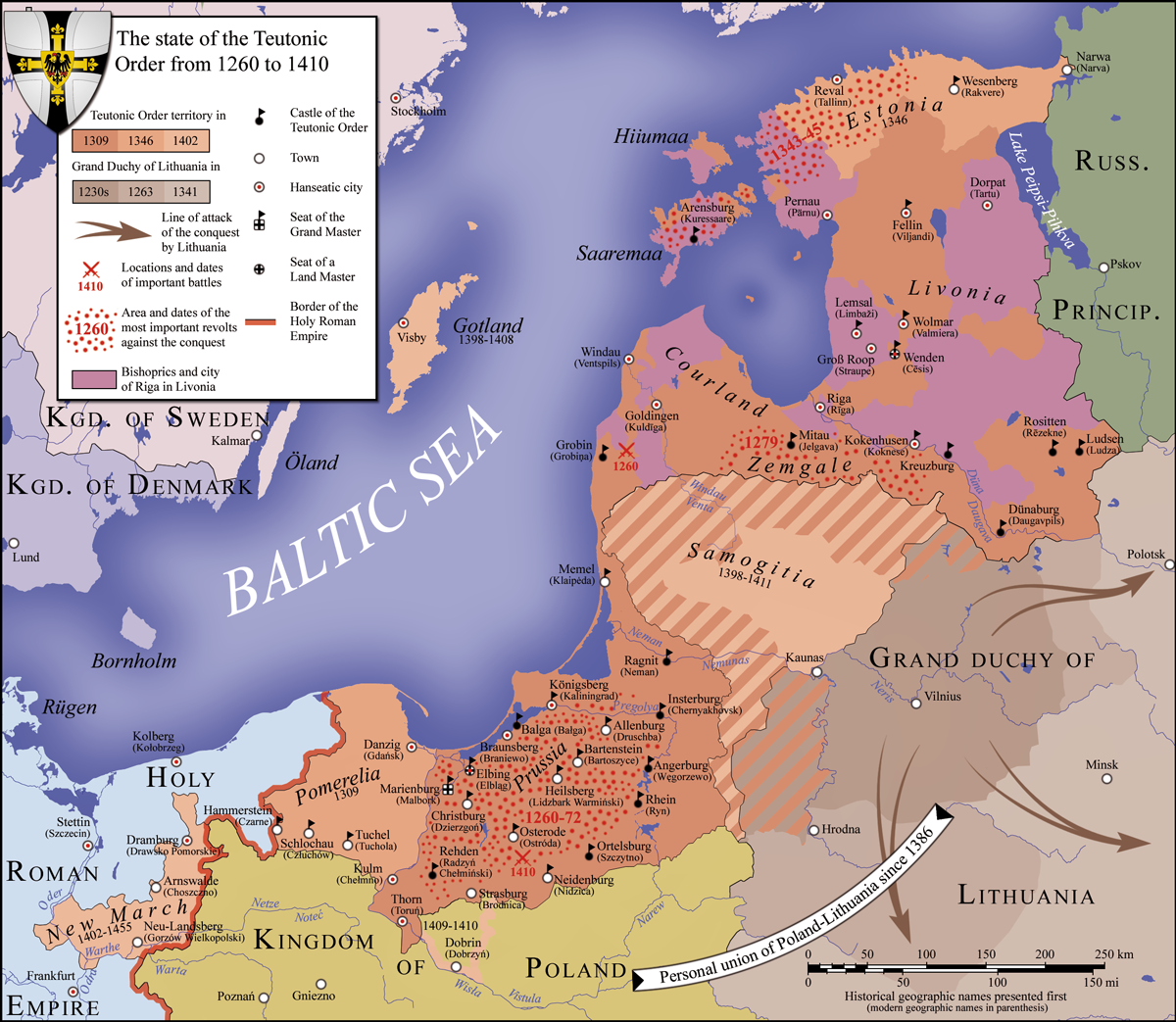

In 1230 CE the Teutonic Order, a crusader order,

after being expelled from Hungary, launched a crusade against the Prussian, Lithuanian and Estonian tribes.

Prussia was dominated by woodlands that made conquest difficult, so the knights raided much and settled little.

Nonetheless they brought much of the eastern Baltic under their control, becoming a major power in the region, together with Poland and Lithuania.

In 1409 CE in Samogitia a rebellion against the knights started.

First Lithuania, then Poland declared support for it.

There was a brief truce but the opposing sides only used it to prepare for war.

They clashed the next year between Grünfelde (Grunwald), Tannenberg (Stebark), and Ludwigsdorf (Łodwigowo, Ludwikowice).

Grunwald was a large battle, however it is unclear how many men each side brought into the fray.

The most widely accepted estimates are 27,000 for the Teutonic order and 39,000 for the Poles and Lithuanians.

The Teutonic Order was in the minority, yet had a strong force of crusader knights,

supplemented by mercenaries like Hungarians and Bohemians, Genoese crossbowmen and English longbowmen.

About 1/3 of this force was infantry, the rest cavalry.

They also had some 100 bombards, but their powder got wet from rain and they fired only two shots in the battle.

The Poles and Lithuanians also fielded allies and mercenaries, including Ruthenians, Czechs and Moravians.

They too brought mostly cavalry, ranging from Polish nobles and Lithuanian boyars to light horsemen.

They even included a contingent of Mongols under Jalal ad-Din.

When the armies met each other at the battlefield, they did not exploit their positions immediately, but instead laboriously lined up in wide fronts, three lines deep.

The Teutonic knights had positioned themselves on the left, opposite light Lithuanian cavalry.

For hours neither side made a move, while the heavily armored knights were taking the worst of the hot summer weather.

Then the Germans provoked the Slavs into attack by having a messenger insult them.

The Lithuanians opened the fighting.

They could not stand against the heavily armored knights and broke.

Some claim that it was a deliberate maneuver, a feigned retreat, but this seems unlikely.

The knights chased the light Slav cavalry to the woods, defeated a Polish reserve and then rejoined the main battle.

In the meanwhile the Poles engaged the Germans too, though they were partially enveloped on their right by the victorious Teutonic left flank.

On the other flank, it was the Poles who pushed the Germans back.

There was heavy fighting, each side taking turns sending in reserves when the situation threatened to become dire for them.

For a moment the knights captured the main Polish banner, which was quickly recaptured.

A while later a lone Teutonic knight managed to break through and charge at the Polish king Jagiełło,

but was killed by a lance thrust from the king's secretary just in time.

The duel had caused a brief pause in the fighting that the Slavs used to reorganize their front.

The Teutonic Order had no more reserves left and was now hard pressed.

Then grand duke Vytautas, together with the braver part of the Lithuanians and Mongols, returned and attacked them in the flank.

The situation for the Germans was hopeless and they started to retreat.

Their army broke into two parts and it became a struggle to survive.

Some units tried to break out, including Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen and his bodyguard.

He was pulled from his horse and killed, like many of the senior members of the order.

Some Germans set up a temporary defense at their camp, aligning wagons in circle, to no avail.

The Poles started to quench their thirst with the wine found in the camp, until king Jagiełło ordered them to resume fighting.

The remnants of the Teutonic Order were chased westward well into the evening.

The Slavs are reported to have killed 8,000, including 300 knights and captured 14,000, while suffering 5,000 dead and 8,000 wounded themselves.

They went on to besiege Marienburg, the capital of the Teutonic Order, but failed.

They were successful at a second battle, at Koronow.

A year later peace was made.

Except for the loss of Samogitia, territorial damage for the Teutonic Order was minimal.

The monetary losses were not.

Dominance in the region shifted from the order to Poland and Lithuania.

War Matrix - Battle of Grunwald

Late Middle Age 1300 CE - 1480 CE, Battles and sieges